Just the other day a philanthropy colleague was sharing their frustration because he was seeing very little movement or visible change on an issue he’s been focusing on for a few years.

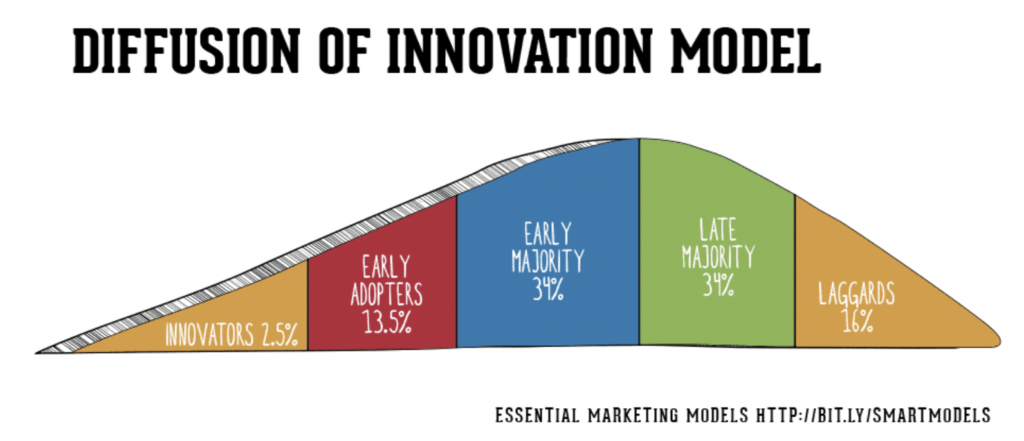

Our conversation made me think of the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, which was developed in the early 1960s by professor Everett Rogers, who wanted to explain how ideas and technology spread. Rogers’ theory proposed that there are categories of adopters of an idea or innovation:

- Innovators: People who are open to risks and the first to try a new idea/innovation

- Early Adopters: People who are comfortable with change and adopting new ideas/innovations

- Early Majority: People who adopt before the average person – they need evidence that the idea/innovation works before adopting

- Late Majority: People who are skeptical of change and only adopt the idea/innovation if it is used by the majority of the population

- Laggards: People who are the last to adopt the idea/innovation and typically are risk-averse and set in their ways

Rogers stated that an idea or innovation reaches critical mass at early majority, or the peak of the bell curve. Things that help a new idea or innovation reach that point are communication channels, social systems, the idea or innovation themselves, and time.

Remember, change takes time.

The theory addresses how time, through a decision-making process by potential adopters, impacts the acceptance or rejection of an idea or innovation. Here’s the process:

- The potential adoptees are exposed to the idea or innovation,

- If interested, they seek additional information,

- They weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the idea or innovation,

- They deploy (or don’t deploy) the idea or innovation,

- Finally, they decide if they will continue using the idea or innovation.

As a person with a public health background, when I think of the Diffusion of Innovation Theory, two health examples immediately come to mind: tobacco control and handwashing.

Tobacco control started in 1954 — 65 years ago — when a study first confirmed the link between smoking and lung cancer. At the time, almost the majority of adults (42.4 percent) were smokers. Smoking also socially acceptable and was prevalent in homes, restaurants, workplaces and airplanes.

That initial study didn’t immediately change behaviors. Consider this timeline:

- 1954: Surgeon General report published linking smoking and lung cancer

- 1970: Cigarette advertising banned on television and radio

- 1987: Aspen, Colorado, becomes first city to ban smoking in restaurants

- 1989: Smoking is banned on airplanes

- 1990: San Luis Obispo, California, becomes the first city to eliminate smoking in all public places

- 1998: The Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement is reached with tobacco industry

It took more than 15 years for the government to take action. It was more than 30 years from the Surgeon General report before a local government took action. Slowly, change started to occur.

Today, only 14 percent of adults are smokers, and the public image of smoking has changed drastically. Can you imagine smoking on a plane or at your desk at work? Additionally, 22,717 municipalities (representing 82 percent of the population), now have smoke-free laws.

Remember, change takes time.

If you thought it took a long time to see change in tobacco use, consider the time it took handwashing to become standard practice.

In 1846, Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweiss was tasked with finding out why many women were dying after childbirth in a hospital. You can read this fascinating account for more details, but the main point is he determined that doctors who had performed autopsies were contaminating women during childbirth, causing them to die from infections. Once doctors began washing their hands, the death toll was significantly reduced.

Despite this discovery, the promotion of handwashing was relatively nonexistent. It wasn’t until the 1970s in the United States when foodborne outbreaks and infections associated with healthcare led to public concern. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention introduced hand-hygiene guidelines in hospitals in 1975 and updated them in 1985.

That’s more 100 years after the doctor identified the benefits of washing hands.

Remember, change takes time. Tobacco control and handwashing are just two examples if this and there are many more examples in the field of technology and industry.

How does this all relate to my colleague’s frustration about not seeing change?

There is a trend in philanthropy and community health of focusing on systems change. My colleague is working on a complex issue and trying to create lasting systems change. We’ve learned that change doesn’t happen overnight, and those working on complicated systems change need to be patient.

Initially focus on innovators and early adopters

There is no surefire way to speed up the process, but I think focusing on the innovators and early adopters is crucial in systems change work. Too often we want the “majority” without engaging and developing the innovators and early adopters. Innovators and early adopters have different characteristics than late majority and laggards. Innovators are willing to take risks and are the first to try an idea. Early adopters are comfortable with change and tend to create opinions about ideas which can help spread ideas.

We think about the adoption categories in our work at the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health. Specially, how do we engage and cultivate champions for community health? How can we engage innovators in pilots or out-of-the-box ideas that can impact health?

In our approach to impacting community health, we are focusing on local communities in Idaho. Specifically, building momentum with champion local elected officials to deepen their knowledge and help them become advocates for community health. We know we have to cultivate the innovators, early adopters, and early majority before we reach critical mass – or the top of the bell curve.

And, of course, we remember that change takes time.